There’s a funny tension in the way we talk about “utility” right now. On one hand, the utilitarian look is having a moment—work pants, chore coats, fatigue pockets, sturdy canvas, and “hardwearing” as a vibe. On the other hand, a lot of those shapes were never meant to be vibes in the first place. They were solutions.

That’s the thing about most menswear: the designs we call “timeless” were rarely born in a showroom. They were born in places where clothes had to earn their keep—factories, ship decks, fields, barracks, and hangars. Sometimes they were born under rules, constraints, or shortages. And then, somehow, they migrated—upward, outward, and everywhere—until they became so familiar we forget where they came from.

If you want to understand why workwear is perpetually “in,” it helps to see menswear as a long history of functional uniforms becoming personal style.

Utility is the Original Design Brief

Consider how many of our staples began as issued gear.

- Chinos / khakis started as military uniforms long before they became weekend defaults. The word khaki is tied to military adoption in the 19th century (British forces in India), and versions of khaki drill became standard across campaigns and eventually across armies.

- Flight jackets were engineered answers to new conditions in the air—lighter materials, warmer insulation, safer mobility in cramped cockpits. The MA-1, for example, was developed for postwar jet-era requirements, then later spilled into civilian wardrobes through surplus, subcultures, and eventually the mainstream.

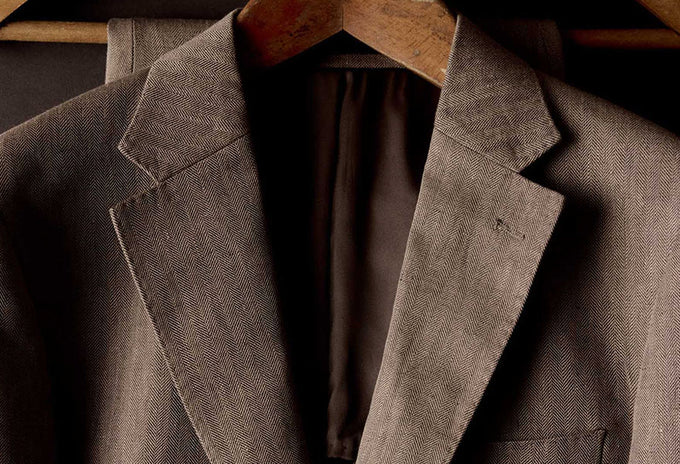

- The chore coat—that tidy, three-pocket workhorse—can be traced to 19th-century France, where the bleu de travail (“blue work”) was dyed to hide stains and built for laborers who needed pockets, durability, and freedom to move.

These garments weren’t “inspired by” utility. They were utility—refined by repetition, standardized by necessity, and made iconic by the way people kept wearing them even after the job was done. Which brings us to one of the most influential style migrations in modern American clothing.

The GI Bill and the Democratization of “Ivy”

The popular shorthand for Ivy style is that it was the wardrobe of elite campuses—blazers, OCBDs, loafers, and all that easy, studied nonchalance. That’s true, but it’s not the whole story. After World War II, American college life changed dramatically. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944—the GI Bill—expanded access to higher education, and campuses filled with veterans who were older than the traditional student, often balancing school with families, jobs, and a very different relationship to “campus life.”

Along with them came a practical wardrobe—especially surplus and military-issue pieces. Those khaki trousers that would become a default Ivy staple weren’t originally part of the prewar collegiate “uniform” in the same way; they arrived in force through returning servicemen and the availability of surplus.

The interesting twist is that this wasn’t just a one-way borrowing, where “Ivy” absorbed military pieces and stayed the same. The style shifted because the people wearing it shifted—more backgrounds, more ages, more lived experience, more practicality. The look didn’t become less Ivy; it became more American.

Why the Utilitarian Look Keeps Coming Back

Every time fashion “discovers” workwear, it frames it as a fresh aesthetic. But the deeper truth is simpler: utility tends to outlast novelty. Workwear survives because it solves problems:

- You can move.

- You can carry things.

- You can layer.

- You can wear it hard without babying it.

- It gets better as it breaks in.

And because these garments were designed for real use, they age in a way that feels honest. A chore coat doesn’t become precious when it’s worn; it becomes itself.

That’s also why surplus and issued gear have always mattered. They’re not just affordable; they’re proven. The postwar spread of khakis across campuses, aided by surplus availability, is a perfect example of that pipeline—from military need, to mass production, to civilian adoption and finally cultural normalization.

This is how a lot of menswear works. Not top-down, but side-to-side: a garment migrates because it’s useful, then it sticks because it looks right, then it becomes “classic” because enough people lived in it long enough for it to feel inevitable.

Honoring the Legacy

Most of the designs we love—fatigues, chinos, field jackets, work shirts, chore coats—became iconic not because they were rare, but because they were common. They were worn daily, repaired, passed down, borrowed, reinterpreted, and taken out of context until the context became broader than any single origin story.

And that’s the point worth holding onto: Menswear isn’t timeless because it avoids history, menswear is timeless because it carries history—quietly, practically, and in plain sight.